Stpries That Start Off Good Get Bad Then Get Good Again

Every story in the world has one of these six basic plots

Researchers analysed over 1700 novels to reveal half-dozen story types – but can they be applied to our most-loved tales? Miriam Quick takes a look.

"My prettiest contribution to the culture" was how the novelist Kurt Vonnegut described his erstwhile principal's thesis in anthropology, "which was rejected because it was so simple and looked like too much fun". The thesis sank without a trace, but Vonnegut connected throughout his life to promote the big idea behind it, which was: "stories have shapes which can be drawn on graph paper".

In a 1995 lecture, Vonnegut chalked out diverse story arcs on a blackboard, plotting how the protagonist'south fortunes change over the course of the narrative on an axis stretching from 'good' to 'ill'. The arcs include 'man in hole', in which the main character gets into trouble then gets out again ("people dear that story, they never get ill of information technology!") and 'boy gets daughter', in which the protagonist finds something wonderful, loses it, then gets it back again at the end. "At that place is no reason why the simple shapes of stories can't be fed into computers", he remarked. "They are beautiful shapes."

"Thanks to new text-mining techniques, this has now been washed. Professor Matthew Jockers at Washington State University, and after researchers at the University of Vermont's Computational Story Lab, analysed data from thousands of novels to reveal half-dozen basic story types – you could call them archetypes – that class the building blocks for more complex stories. The Vermont researchers describe the six story shapes behind more than 1700 English novels every bit:

ane. Rags to riches – a steady ascent from bad to adept fortune

ii. Riches to rags – a fall from practiced to bad, a tragedy

3. Icarus – a rise so a fall in fortune

4. Oedipus – a autumn, a ascension and so a fall over again

5. Cinderella – rise, fall, rise

6. Homo in a hole – fall, rise

The researchers used sentiment analysis to go the data – a statistical technique often used by marketeers to analyse social media posts in which each word is allocated a item 'sentiment score', based on crowdsourced data. Depending on the lexicon chosen, a give-and-take tin exist categorised as positive (happy) or negative (sad), or it tin can be associated with one or more of viii more subtle emotions, including fear, joy, surprise and apprehension. For instance, the give-and-take 'happy' is positive, and associated with joy, trust and anticipation. The word 'cancel' is negative and associated with acrimony.

Do sentiment analysis on all the words in a novel, verse form or play and plot the results against time, and it's possible to encounter how the mood changes over the course of the text, revealing a kind of emotional narrative. While not a perfect tool – it looks at words in isolation, ignoring context – it tin can be surprisingly insightful when applied to larger chunks of text, as this blog mail service on Jane Austen novels from data scientist Julia Silge shows. The tools to practise sentiment analysis are freely bachelor, and much out-of-copyright literature can be downloaded from online repository Project Gutenberg. We looked at some of the all-time-loved tales from BBC Culture'south 100 stories that shaped the world poll to attempt and find the six story types.

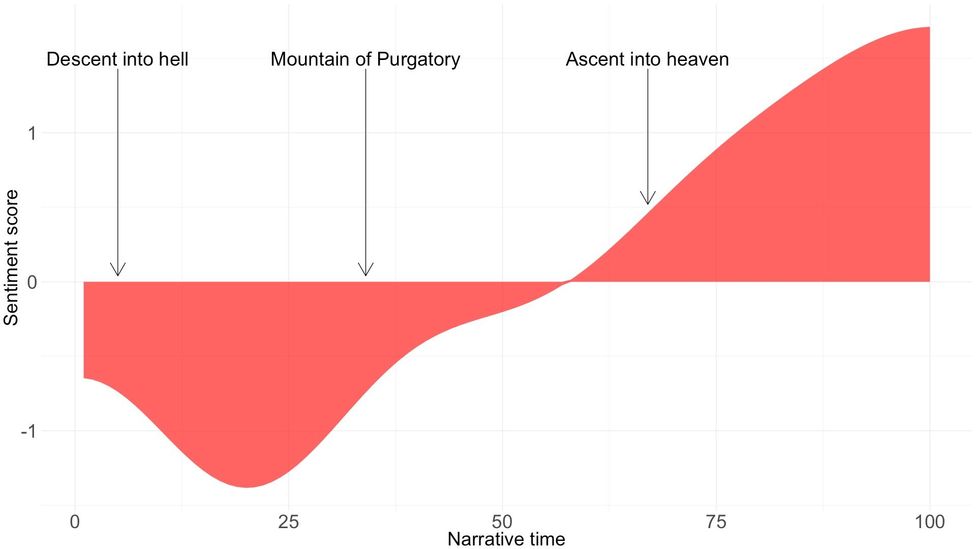

The Divine Comedy (Dante Alighieri, 1308-1320)

Translated by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Story type: Rags to riches

(Credit: Nautical chart by Miriam Quick, created using R packages Syuzhet, Tidytext and Gutenbergr. All charts utilise smoothed data)

Dante'due south tightly structured, exquisitely symmetrical epic poem traces his imaginary journey down into hell in the Inferno, accompanied past – who else? – the poet Virgil. Sure enough, things commencement off badly in the Divine One-act with a low sentiment score that sinks further as the duo descend through the circles of hell. (There is a trace of 'man in a hole' here, which in this instance is as literally true as things could be in such an allegorical text.) Having miraculously survived hell, they adjacent climb the Mountain of Purgatory where the souls of the excommunicated, slothful and lustful reside, and Beatrice – Dante's ideal woman – eventually replaces Virgil equally his companion. The pair's ascent into heaven in the Paradiso is marked by growing joy as the poet comprehends the true nature of virtue and his soul becomes one with "the Dearest which moves the sun and the other stars".

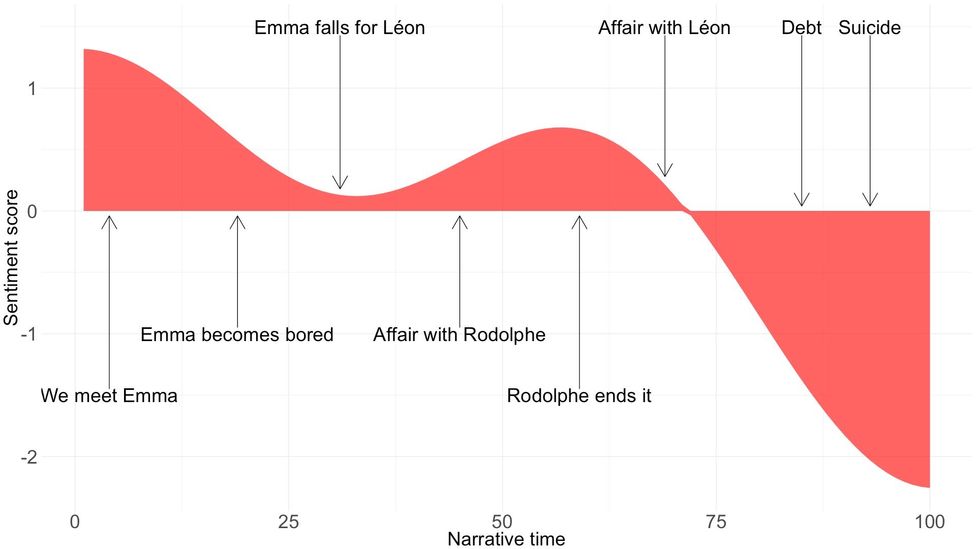

Madame Bovary (Gustave Flaubert, 1856)

Translated by Eleanor Marx-Aveling

Story type: Riches to rags

(Credit: Chart by Miriam Quick, created using R packages Syuzhet, Tidytext and Gutenbergr. All charts apply smoothed data)

There's a moment in Flaubert's tale of a bored and faithless housewife where our protagonist Emma Bovary muses that, since her life so far has been then bad, the part still to be lived must surely be better.

Not then. Emma embarks on failed, desperate love diplomacy that offering only brief respite from the grinding tedium of being an imaginative adult female married to the globe's dullest man, mounts up catastrophic debts and finally, kills herself by drinking arsenic. Her grieving husband, later on discovering her multiple infidelities, then dies besides, and their now-orphaned daughter is sent to live with her grandmother, who also dies. The little girl goes to alive with a poor aunt, who sends her to work in a cotton manufactory. It's a textbook tragedy, driven with relentless focus towards the terminate goal of full downfall, and an utterly satisfying story.

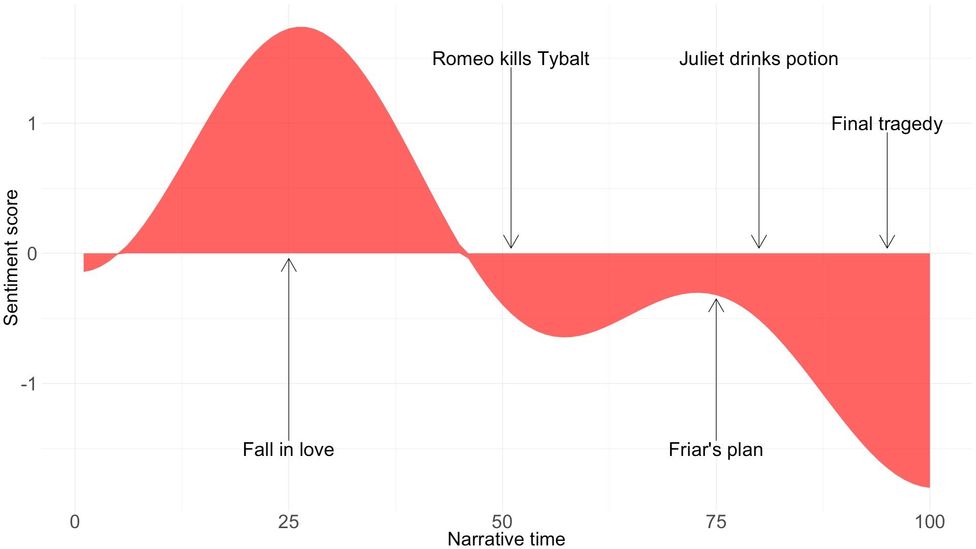

Romeo and Juliet (William Shakespeare, 1597)

Story type: Icarus

(Credit: Chart by Miriam Quick, created using R packages Syuzhet, Tidytext and Gutenbergr. All charts utilise smoothed data)

Romeo and Juliet is naturally considered to be a tragedy in line with Shakespeare's own description, just when you analyse its sentiment the story appears closer to the Icarus shape: a rise, and so a fall. After all, the boy must notice the girl and fall in love with her before they both lose each other. The romantic peak happens around a quarter of the manner through the play, in the famous balcony scene in which they declare their undying love for i some other.

Information technology's all downhill from there. Romeo kills Tybalt and flees, the Friar's program to smuggle Juliet out to join him provides a pocket-sized bump of fake promise to the drama, just once Juliet has drunk the potion nothing can prevent the terminal, still-searing tragedy.

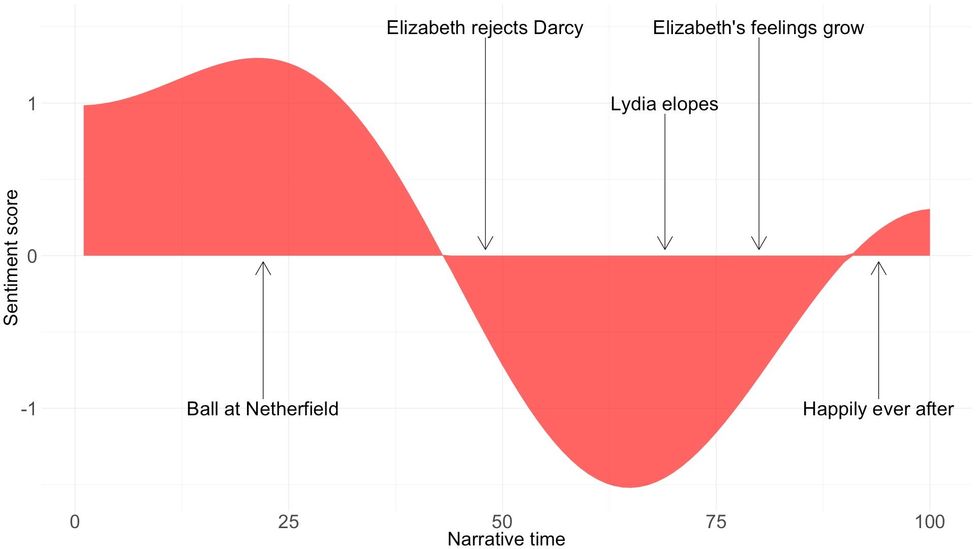

Pride and Prejudice (Jane Austen, 1813)

Story type: Man in a hole or Cinderella

(Credit: Chart by Miriam Quick, created using R packages Syuzhet, Tidytext and Gutenbergr. All charts utilise smoothed data)

The starting time one-half of Austen'due south sparkling novel is a fiesta of balls and loftier jinks (albeit restrained ones), witticisms and unserious marriage proposals from the likes of comical vicar Mr Collins. Things take a darker turn every bit Bingley leaves and Elizabeth starts to develop a dislike for Darcy (based on a misunderstanding, naturally). The novel's sentiment pivots into decisively negative territory after his disastrous proposal, reaching its nadir every bit Lydia elopes with the untrustworthy Wickham. This, of grade, is also Darcy's opportunity to prove himself, which he does with dignity and aplomb, winning Elizabeth'due south heart and ensuring a measured happy ending, in which everyone is slightly wiser than they were before.

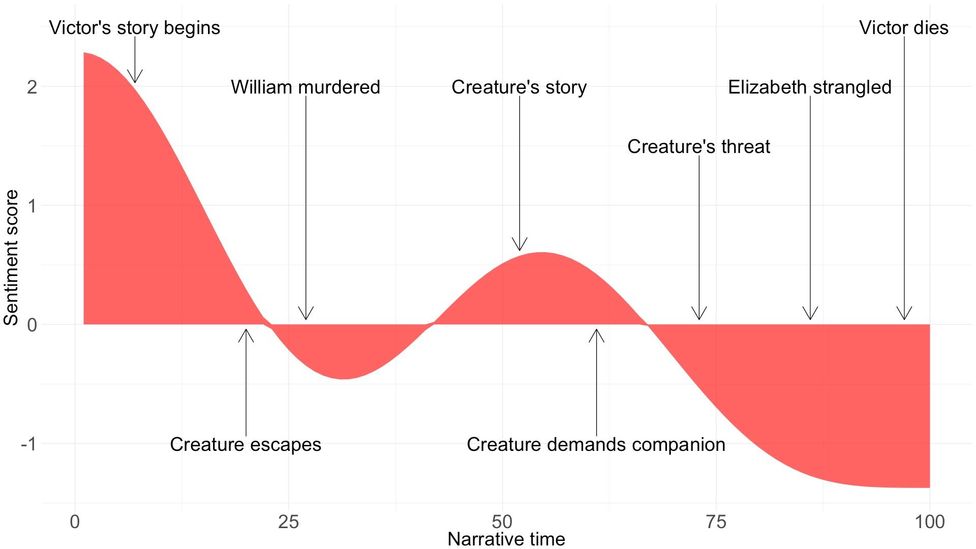

Frankenstein (Mary Shelley, 1818)

Story type: Oedipus

(Credit: Chart past Miriam Quick, created using R packages Syuzhet, Tidytext and Gutenbergr. All charts utilise smoothed data)

Shelley's seminal novel tells the woeful tale of Victor Frankenstein'southward Creature in Victor's own words, equally related by Helm Walton in a series of letters to his sister. At i point, the Brute gets to have over the narrative, making the novel a story within a story within a story. This is in fact a moment of respite in what is overall a downward trajectory from the happy description of his early life with which Victor opens his narrative, to the appalling ending. At a pivotal moment two thirds of the mode through the novel, the Brute offers Victor a way out – make him a female companion. But Victor refuses. From this signal on, his fate is sealed. "Remember, I shall be with you on your wedding-dark", threatens the Creature. And so it proves.

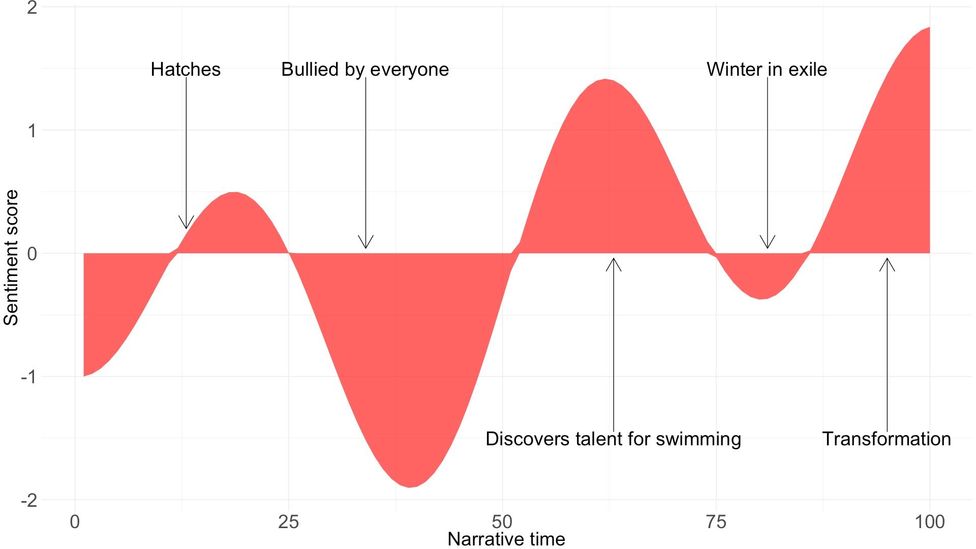

The Ugly Duckling (Hans Christian Andersen, 1843)

Translated by HP Paull

Story blazon: Complex

(Credit: Chart by Miriam Quick, text source: Wikisource, created using R packages Syuzhet, Tidytext and Gutenbergr. All charts use smoothed data)

The shortest story of them all, Hans Christian Andersen'south famous fairy tale besides has the about complex construction, incorporating 2 human being in a hole (or duck in a hole) sentiment arcs inside an overall rags to riches narrative framework. That is, things go generally meliorate for the duckling over the course of the story, only there are flashes of light and dark along the way: he hatches (yay!) only is bullied for being unlike (boo). He discovers he can swim better than the other ducks and experiences a premonition of affinity every bit a group of swans fly over (yay!), simply then well-nigh dies in the wintertime cold (boo). He does become a swan eventually, in a mode entirely foretold from the beginning. That's the point, of course: "To exist built-in in a duck'southward nest, in a farmyard, is of no issue to a bird, if information technology is hatched from a swan's egg." The story ends on the highest of notes, with the swan-all-along crying that he "never dreamed of such happiness equally this".

BBC Civilization'south Stories that Shaped the World series looks at ballsy poems, plays and novels from around the globe that have influenced history and changed mindsets. The poll of writers and critics, 100 Stories that Shaped the Earth, will be discussed at the Hay Festival in May and subsequently circulate on BBC Globe News.

If y'all would similar to annotate on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Civilisation, caput over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter .

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter , called "If You Only Read six Things This Week". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Uppercase and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Source: https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20180525-every-story-in-the-world-has-one-of-these-six-basic-plots