According to What You Know About Kant, Why Would Breaking a Contract Be Wrong?

Kantian ethics refers to a deontological ethical theory adult by High german philosopher Immanuel Kant that is based on the notion that: "It is impossible to think of anything at all in the globe, or indeed even beyond it, that could exist considered proficient without limitation except a good will." The theory was developed as a upshot of Enlightenment rationalism, stating that an activeness can only exist correct if its maxim—the principle behind it—is duty to the moral law, and arises from a sense of duty in the actor.

Cardinal to Kant's structure of the moral police force is the categorical imperative, which acts on all people, regardless of their interests or desires. Kant formulated the chiselled imperative in various ways. His principle of universalizability requires that, for an activeness to be permissible, it must be possible to employ it to all people without a contradiction occurring. Kant's conception of humanity, the second section of the chiselled imperative, states that as an finish in itself, humans are required never to treat others merely equally a means to an end, but always every bit ends in themselves. The formulation of autonomy concludes that rational agents are spring to the moral police force by their own volition, while Kant's concept of the Kingdom of Ends requires that people deed as if the principles of their actions constitute a police force for a hypothetical kingdom. Kant also distinguished betwixt perfect and imperfect duties. Kant used the example of lying equally an application of his ethics: because there is a perfect duty to tell the truth, we must never lie, even if it seems that lying would bring about better consequences than telling the truth. Too, a perfect duty (e.chiliad. the duty non to lie) always holds truthful; an imperfect duty (east.g., the duty to give to charity) tin can be made flexible and applied in particular fourth dimension and identify.

Those influenced by Kantian ethics include social philosopher Jürgen Habermas, political philosopher John Rawls, and psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan. German language philosopher K. Westward. F. Hegel criticised Kant for non providing specific enough detail in his moral theory to touch controlling and for denying homo nature. The Cosmic Church has criticized Kant'south ethics as contradictory, and regards Christian ethics as more than uniform with virtue ideals. German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, arguing that ethics should attempt to describe how people behave, criticised Kant for existence prescriptive. Marcia Baron has defended the theory past arguing that duty does not diminish other motivations.

The claim that all humans are due nobility and respect equally autonomous agents necessitates that medical professionals should exist happy for their treatments to be performed on anyone, and that patients must never be treated merely as useful for gild. Kant's approach to sexual ethics emerged from his view that humans should never be used merely equally a means to an end, leading him to regard sexual activeness as degrading, and to condemn certain specific sexual practices—for example, extramarital sex. Accordingly, some feminist philosophers have used Kantian ethics to condemn practices such as prostitution and pornography, which care for women as ways alone. Kant besides believed that, because animals practice not possess rationality, we cannot have duties to them except indirect duties non to develop immoral dispositions through cruelty towards them.

Outline [edit]

Although all of Kant's work develops his ethical theory, information technology is virtually clearly divers in Background of the Metaphysics of Morals, Critique of Practical Reason, and Metaphysics of Morals. Equally part of the Enlightenment tradition, Kant based his ethical theory on the belief that reason should be used to determine how people ought to human activity.[one] He did not endeavor to prescribe specific activity, but instructed that reason should exist used to decide how to behave.[2]

Skillful will and Duty [edit]

In his combined works, Kant synthetic the basis for an ethical police by the concept of duty.[3] Kant began his ethical theory by arguing that the only virtue that tin be unqualifiedly skilful is a adept will. No other virtue has this status considering every other virtue tin be used to achieve immoral ends (for instance, the virtue of loyalty is not good if one is loyal to an evil person). The good will is unique in that it is always good and maintains its moral value even when it fails to achieve its moral intentions.[iv] Kant regarded the skillful will as a unmarried moral principle that freely chooses to apply the other virtues for moral ends.[5]

For Kant, a good will is a broader conception than a will that acts from duty. A will that acts from duty is distinguishable equally a will that overcomes hindrances in order to go on the moral law. A dutiful will is thus a special case of a good will that becomes visible in adverse conditions. Kant argues that just acts performed with regard to duty have moral worth. This is not to say that acts performed merely in accordance with duty are worthless (these still deserve approval and encouragement), simply that special esteem is given to acts that are performed out of duty.[6]

Kant'southward conception of duty does not entail that people perform their duties grudgingly. Although duty often constrains people and prompts them to human action confronting their inclinations, it still comes from an amanuensis'southward volition: they desire to keep the moral law. Thus, when an agent performs an activity from duty it is considering the rational incentives thing to them more than their opposing inclinations. Kant wished to motility across the conception of morality as externally imposed duties, and present an ideals of autonomy, when rational agents freely recognize the claims reason makes upon them.[7]

Perfect and imperfect duties [edit]

Applying the categorical imperative, duties arise because failure to fulfill them would either result in a contradiction in conception or in a contradiction in the volition. The former are classified as perfect duties, the latter every bit imperfect. A perfect duty always holds true. Kant eventually argues that at that place is in fact only one perfect duty -- The Categorical Imperative. An imperfect duty allows flexibility—beneficence is an imperfect duty because nosotros are not obliged to be completely beneficent at all times, only may choose the times and places in which we are.[8] Kant believed that perfect duties are more than important than imperfect duties: if a conflict between duties arises, the perfect duty must exist followed.[9]

Chiselled Imperative [edit]

The principal conception of Kant's ethics is the categorical imperative,[10] from which he derived four farther formulations.[11] Kant made a distinction between categorical and hypothetical imperatives. A hypothetical imperative is 1 that nosotros must obey if we want to satisfy our desires: 'go to the doctor' is a hypothetical imperative because we are but obliged to obey information technology if we want to go well. A chiselled imperative binds united states regardless of our desires: everyone has a duty to non lie, regardless of circumstances and even if it is in our interest to do and so. These imperatives are morally binding because they are based on reason, rather than contingent facts about an amanuensis.[12] Unlike hypothetical imperatives, which demark u.s. insofar as nosotros are function of a group or order which we owe duties to, we cannot opt out of the categorical imperative because we cannot opt out of beingness rational agents. Nosotros owe a duty to rationality by virtue of being rational agents; therefore, rational moral principles apply to all rational agents at all times.[thirteen]

Universalizability [edit]

Kant's first formulation of the Categorical Imperative is that of universalizability:[fourteen]

Act only according to that maxim by which you can at the same fourth dimension will that it should go a universal law.

When someone acts, it is co-ordinate to a rule, or proverb. For Kant, an act is only permissible if one is willing for the proverb that allows the action to be a universal law past which everyone acts.[15] Maxims fail this test if they produce either a contradiction in formulation or a contradiction in the volition when universalized. A contradiction in formulation happens when, if a proverb were to be universalized, it ceases to make sense, because the "maxim would necessarily destroy itself every bit before long as it was made a universal law."[16] For example, if the maxim 'It is permissible to intermission promises' was universalized, no one would trust whatever promises made, so the idea of a promise would get meaningless; the maxim would be self-contradictory considering, when universalized, promises cease to exist meaningful. The maxim is not moral considering it is logically impossible to universalize—nosotros could non conceive of a world where this maxim was universalized.[17]

A saying can also be immoral if it creates a contradiction in the volition when universalized. This does not mean a logical contradiction, but that universalizing the maxim leads to a state of affairs that no rational being would desire. For example, Julia Commuter argues that the saying 'I volition not requite to clemency' produces a contradiction in the will when universalized considering a world where no one gives to clemency would be undesirable for the person who acts by that proverb.[18]

Kant believed that morality is the objective law of reason: just as objective physical laws necessitate concrete deportment (e.grand., apples fall down because of gravity), objective rational laws necessitate rational actions. He thus believed that a perfectly rational being must besides be perfectly moral, because a perfectly rational being subjectively finds information technology necessary to do what is rationally necessary. Because humans are not perfectly rational (they partly deed past instinct), Kant believed that humans must arrange their subjective volition with objective rational laws, which he called conformity obligation.[nineteen] Kant argued that the objective constabulary of reason is a priori, existing externally from rational being. Just as physical laws exist prior to physical beings, rational laws (morality) exist prior to rational beings. Therefore, co-ordinate to Kant, rational morality is universal and cannot change depending on circumstance.[20]

Some have postulated a similarity betwixt the first conception of the Categorical Imperative and the Gilt Rule.[21] [22] Kant himself criticized the Golden Dominion as neither purely formal nor necessarily universally binding.[23]

Humanity as an end in itself [edit]

Kant's 2nd formulation of the Chiselled Imperative is to treat humanity as an stop in itself:

Human action in such a way that y'all treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of some other, always at the aforementioned time every bit an end and never simply as a ways.

Kant argued that rational beings tin can never exist treated only as ways to ends; they must always also exist treated as ends themselves, requiring that their own reasoned motives must be equally respected. This derives from Kant's merits that reason motivates morality: it demands that we respect reason as a motive in all beings, including other people. A rational being cannot rationally consent to be used but as a ways to an stop, so they must always be treated equally an stop.[25] Kant justified this by arguing that moral obligation is a rational necessity: that which is rationally willed is morally right. Because all rational agents rationally will themselves to be an stop and never but a means, information technology is morally obligatory that they are treated as such.[26] This does not mean that nosotros tin can never treat a human as a means to an finish, but that when we do, we likewise treat them equally an end in themselves.[25]

Formula of Autonomy [edit]

Kant's formula of autonomy expresses the idea that an agent is obliged to follow the Chiselled Imperative considering of their rational will, rather than any exterior influence. Kant believed that any moral law motivated by the desire to fulfill another interest would deny the Categorical Imperative, leading him to argue that the moral law must but ascend from a rational volition.[27] This principle requires people to recognize the right of others to act autonomously and means that, equally moral laws must exist universalizable, what is required of one person is required of all.[28] [29] [30]

Kingdom of Ends [edit]

Another formulation of Kant's Categorical Imperative is the Kingdom of Ends:

A rational being must always regard himself as giving laws either equally fellow member or as sovereign in a kingdom of ends which is rendered possible by the liberty of volition.

This formulation requires that actions be considered as if their maxim is to provide a law for a hypothetical Kingdom of Ends. Accordingly, people have an obligation to human action upon principles that a customs of rational agents would accept every bit laws.[32] In such a community, each private would only have maxims that tin can govern every fellow member of the community without treating any fellow member merely as a ways to an end.[33] Although the Kingdom of Ends is an ideal—the deportment of other people and events of nature ensure that actions with skilful intentions sometimes result in harm—we are still required to deed categorically, every bit legislators of this ideal kingdom.[34]

Influences on Kantian ideals [edit]

Biographer of Kant, Manfred Kuhn, suggested that the values Kant'due south parents held, of "hard work, honesty, cleanliness, and independence", set him an instance and influenced him more than than their pietism did. In the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Michael Rohlf suggests that Kant was influenced by his instructor, Martin Knutzen, himself influenced by the piece of work of Christian Wolff and John Locke, and who introduced Kant to the piece of work of English language physicist Isaac Newton.[35] Eric Entrican Wilson and Lara Denis emphasize David Hume'due south influence on Kant's ethics. Both of them try to reconcile freedom with a delivery to causal determinism and believe that morality'southward foundation is independent of religion.[36]

Louis Pojman has suggested four strong influences on Kant's ethics:

- Lutheran Pietism, to which Kant's parents subscribed, emphasised honesty and moral living over doctrinal belief, more concerned with feeling than rationality. Kant believed that rationality is required, but that it should be concerned with morality and good volition. Kant's description of moral progress as the turning of inclinations towards the fulfilment of duty has been described as a version of the Lutheran doctrine of sanctification.[37]

- Political philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose Social Contract influenced Kant's view on the fundamental worth of homo beings. Pojman likewise cites gimmicky upstanding debates as influential to the development of Kant's ethics. Kant favoured rationalism over empiricism, which meant he viewed morality equally a form of knowledge, rather than something based on human desire.

- Natural law, the belief that the moral law is determined past nature.[38]

- Intuitionism, the belief that humans take intuitive awareness of objective moral truths.[38]

Influenced past Kantian ideals [edit]

Karl Marx [edit]

Philip J. Kain believes that, although Karl Marx rejected many of the ideas and assumptions institute in Kant's ethical writings, his views about universalization are much like Kant's views nearly the categorical imperative, and his concept of freedom is similar to Kant's concept of freedom. Marx has as well been influenced by Kant in his theory of Communist order, which is established by a historical agent that will make possible the realization of morality.[39]

Jürgen Habermas [edit]

Photograph of Jurgen Habermas, whose theory of discourse ethics was influenced by Kantian ideals

German language philosopher Jürgen Habermas has proposed a theory of soapbox ethics that he claims is a descendant of Kantian ethics.[40] He proposes that action should be based on advice between those involved, in which their interests and intentions are discussed so they can be understood past all. Rejecting whatever form of coercion or manipulation, Habermas believes that agreement between the parties is crucial for a moral conclusion to be reached.[41] Similar Kantian ethics, soapbox ethics is a cognitive ethical theory, in that it supposes that truth and falsity tin can be attributed to ethical propositions. It also formulates a rule past which ethical deportment can exist determined and proposes that ethical deportment should be universalizable, in a similar mode to Kant's ideals.[42]

Habermas argues that his upstanding theory is an improvement on Kant's,[42] and rejects the dualistic framework of Kant's ethics. Kant distinguished between the phenomena world, which tin be sensed and experienced by humans, and the noumena, or spiritual world, which is inaccessible to humans. This dichotomy was necessary for Kant because information technology could explain the autonomy of a man agent: although a human is bound in the astounding world, their actions are costless in the intelligible world. For Habermas, morality arises from discourse, which is fabricated necessary by their rationality and needs, rather than their liberty.[43]

Karl Popper [edit]

Karl Popper modified Kant'southward ideals and focused on the subjective dimensions of his moral theory. Like Kant, Popper believed that morality cannot exist derived from human being nature and that moral virtue is not identical to self-interest. He radicalized Kant'southward formulation of autonomy, eliminating its naturalistic and psychologistic elements. He argued that the categorical imperative cannot be justified through rational nature or pure motives. Because Kant presupposed universality and lawfulness that cannot be proven, his transcendental deduction fails in ethics equally in epistemology.[44]

John Rawls [edit]

The social contract theory of political philosopher John Rawls, adult in his work A Theory of Justice, was influenced by Kant'due south ideals.[45] Rawls argued that a just society would exist fair. To achieve this fairness, he proposed a hypothetical moment prior to the existence of a club, at which the lodge is ordered: this is the original position. This should take place from behind a veil of ignorance, where no i knows what their ain position in club will exist, preventing people from being biased by their own interests and ensuring a fair result.[46] Rawls' theory of justice rests on the belief that individuals are free, equal, and moral; he regarded all human beings as possessing some degree of reasonableness and rationality, which he saw as the constituents of morality and entitling their possessors to equal justice. Rawls dismissed much of Kant's dualisms, arguing that the structure of Kantian ethics, once reformulated, is clearer without them—he described this as one of the goals of A Theory of Justice.[47]

Jacques Lacan [edit]

French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan linked psychoanalysis with Kantian ideals in his works The Ethics of Psychoanalysis and Kant avec Sade, comparing Kant with the Marquis de Sade.[48] Lacan argued that Sade's maxim of jouissance—the pursuit of sexual pleasure or enjoyment—is morally adequate by Kant's criteria considering it can be universalised. He proposed that, while Kant presented human freedom equally critical to the moral law, Sade farther argued that human freedom is simply fully realised through the maxim of jouissance.[49]

Thomas Nagel [edit]

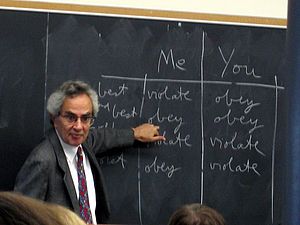

Nagel in 2008, didactics ethics

Thomas Nagel has been highly influential in the related fields of moral and political philosophy. Supervised by John Rawls, Nagel has been a long-standing proponent of a Kantian and rationalist approach to moral philosophy. His distinctive ideas were first presented in the short monograph The Possibility of Altruism, published in 1970. That book seeks by reflection on the nature of practical reasoning to uncover the formal principles that underlie reason in exercise and the related general beliefs about the self that are necessary for those principles to be truly applicative to the states.

Nagel defends motivated desire theory nearly the motivation of moral activeness. Co-ordinate to motivated desire theory, when a person is motivated to moral action it is indeed true that such actions are motivated—like all intentional actions—by a belief and a desire. But it is important to become the justificatory relations correct: when a person accepts a moral judgment he or she is necessarily motivated to human action. Only it is the reason that does the justificatory work of justifying both the action and the desire. Nagel contrasts this view with a rival view which believes that a moral agent tin can only accept that he or she has a reason to act if the want to acquit out the action has an independent justification. An account based on presupposing sympathy would be of this kind.[fifty]

The virtually hitting claim of the book is that in that location is a very close parallel betwixt prudential reasoning in ane's own interests and moral reasons to act to further the interests of some other person. When one reasons prudentially, for example about the hereafter reasons that one will have, ane allows the reason in the future to justify one's electric current activity without reference to the forcefulness of one's current desires. If a hurricane were to destroy someone's car next yr at that point he will want his insurance company to pay him to supersede information technology: that future reason gives him a reason, now, to accept out insurance. The strength of the reason ought not to be hostage to the strength of one'south current desires. The denial of this view of prudence, Nagel argues, ways that 1 does not really believe that one is 1 and the same person through fourth dimension. One is dissolving oneself into distinct person-stages.[51]

Gimmicky Kantian ethicists [edit]

Onora O'Neill [edit]

Philosopher Onora O'Neill, who studied nether John Rawls at Harvard Academy, is a contemporary Kantian ethicist who supports a Kantian approach to issues of social justice. O'Neill argues that a successful Kantian account of social justice must not rely on whatsoever unwarranted idealizations or assumption. She notes that philosophers have previously charged Kant with idealizing humans as autonomous beings, without whatsoever social context or life goals, though maintains that Kant'southward ideals can be read without such an idealization.[52] O'Neill prefers Kant'due south conception of reason as practical and bachelor to be used by humans, rather than as principles attached to every human existence. Conceiving of reason as a tool to make decisions with ways that the just thing able to restrain the principles we adopt is that they could exist adopted by all. If we cannot will that anybody adopts a certain principle, then we cannot give them reasons to adopt it. To use reason, and to reason with other people, nosotros must reject those principles that cannot be universally adopted. In this fashion, O'Neill reached Kant's formulation of universalisability without adopting an idealistic view of human autonomy.[53] This model of universalisability does not crave that we prefer all universalisable principles, just simply prohibits us from adopting those that are non.[54]

From this model of Kantian ethics, O'Neill begins to develop a theory of justice. She argues that the rejection of certain principles, such as deception and compulsion, provides a starting point for basic conceptions of justice, which she argues are more determinate for homo beings that the more than abstract principles of equality or freedom. Nevertheless, she concedes that these principles may seem to be excessively demanding: in that location are many actions and institutions that practice rely on non-universalisable principles, such equally injury.[55]

Marcia Baron [edit]

In his paper "The Schizophrenia of Modernistic Ethical Theories", philosopher Michael Stocker challenges Kantian ethics (and all modern ethical theories) by arguing that deportment from duty lack certain moral value. He gives the example of Smith, who visits his friend in hospital out of duty, rather than because of the friendship; he argues that this visit seems morally lacking because it is motivated by the wrong thing.[56]

Marcia Baron has attempted to defend Kantian ethics on this point. Later presenting a number of reasons that we might find interim out of duty objectionable, she argues that these problems only arise when people distort what their duty is. Acting out of duty is non intrinsically incorrect, but immoral consequences tin can occur when people misunderstand what they are duty-leap to do. Duty need not be seen as common cold and impersonal: i may take a duty to cultivate their grapheme or improve their personal relationships.[57] Baron farther argues that duty should exist construed equally a secondary motive—that is, a motive that regulates and sets conditions on what may be done, rather than prompt specific deportment. She argues that, seen this way, duty neither reveals a deficiency in one's natural inclinations to act, nor undermines the motives and feelings that are essential to friendship. For Baron, being governed by duty does non mean that duty is ever the primary motivation to act; rather, it entails that considerations of duty are e'er action-guiding. A responsible moral agent should take an involvement in moral questions, such every bit questions of graphic symbol. These should guide moral agents to act from duty.[58]

Criticisms of Kantian ethics [edit]

Friedrich Schiller [edit]

While Friedrich Schiller appreciated Kant for basing the source of morality on a person'south reason rather than on God, he also criticized Kant for non going far enough in the conception of autonomy, as the internal constraint of reason would also take away a person's autonomy past going against their sensuous cocky. Schiller introduced the concept of the "beautiful soul," in which the rational and non-rational elements inside a person are in such harmony that a person tin can be led entirely past his sensibility and inclinations. "Grace" is the expression in appearance of this harmony. However, given that humans are not naturally virtuous, information technology is in exercising command over the inclinations and impulses through moral strength that a person displays "dignity." Schiller's main implied criticism of Kant is that the latter only saw dignity while grace is ignored.[59]

Kant responded to Schiller in a footnote that appears in Faith inside the Bounds of Bare Reason. While he admits that the concept of duty can only be associated with nobility, gracefulness is also allowed by the virtuous individual every bit he attempts to meet the demands of the moral life courageously and joyously.[sixty]

Grand. Due west. F. Hegel [edit]

Portrait of Chiliad. West. F. Hegel

German philosopher G. W. F. Hegel presented two main criticisms of Kantian ideals. He commencement argued that Kantian ideals provides no specific information about what people should do because Kant'due south moral constabulary is solely a principle of non-contradiction.[2] He argued that Kant'due south ethics lack whatsoever content and then cannot establish a supreme principle of morality. To illustrate this point, Hegel and his followers have presented a number of cases in which the Formula of Universal Police either provides no meaningful answer or gives an plainly wrong reply. Hegel used Kant'southward example of existence trusted with another man'south money to debate that Kant'south Formula of Universal Law cannot determine whether a social system of belongings is a morally good thing, because either answer tin can entail contradictions. He also used the example of helping the poor: if everyone helped the poor, in that location would exist no poor left to aid, so beneficence would exist impossible if universalised, making it immoral according to Kant'southward model.[61] Hegel'south second criticism was that Kant's ideals forces humans into an internal disharmonize between reason and desire. For Hegel, it is unnatural for humans to suppress their desire and subordinate it to reason. This means that, by non addressing the tension between self-involvement and morality, Kant'southward ethics cannot give humans whatever reason to be moral.[62]

Arthur Schopenhauer [edit]

German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer criticised Kant's belief that ethics should concern what ought to exist done, insisting that the telescopic of ideals should be to endeavour to explain and translate what actually happens. Whereas Kant presented an idealized version of what ought to be done in a perfect world, Schopenhauer argued that ethics should instead exist practical and arrive at conclusions that could work in the real world, capable of being presented every bit a solution to the world'southward problems.[63] Schopenhauer drew a parallel with aesthetics, arguing that in both cases prescriptive rules are not the most important role of the discipline. Considering he believed that virtue cannot exist taught—a person is either virtuous or is not—he bandage the proper place of morality as restraining and guiding people's beliefs, rather than presenting unattainable universal laws.[64]

Friedrich Nietzsche [edit]

Philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche criticised all gimmicky moral systems, with a special focus on Christian and Kantian ethics. He argued that all mod ethical systems share two problematic characteristics: showtime, they make a metaphysical claim well-nigh the nature of humanity, which must be accepted for the system to have any normative force; and second, the arrangement benefits the interests of certain people, often over those of others. Although Nietzsche's main objection is not that metaphysical claims about humanity are untenable (he also objected to upstanding theories that practice not make such claims), his two primary targets—Kantianism and Christianity—do make metaphysical claims, which therefore feature prominently in Nietzsche's criticism.[65]

Nietzsche rejected cardinal components of Kant'south ethics, specially his argument that morality, God, and immorality, tin can be shown through reason. Nietzsche cast suspicion on the use of moral intuition, which Kant used as the foundation of his morality, arguing that it has no normative force in ethics. He further attempted to undermine fundamental concepts in Kant's moral psychology, such every bit the volition and pure reason. Similar Kant, Nietzsche developed a concept of autonomy; however, he rejected Kant'south idea that valuing our own autonomy requires us to respect the autonomy of others.[66] A naturalist reading of Nietzsche'south moral psychology stands contrary to Kant's formulation of reason and desire. Under the Kantian model, reason is a fundamentally unlike motive to desire considering it has the capacity to stand back from a state of affairs and make an independent decision. Nietzsche conceives of the self as a social construction of all our dissimilar drives and motivations; thus, when it seems that our intellect has made a decision against our drives, it is actually only an alternative drive taking authority over another. This is in straight contrast with Kant'due south view of the intellect as opposed to instinct; instead, it is just another instinct. In that location is thus no self-capable of standing back and making a decision; the decision the cocky-makes is merely determined by the strongest bulldoze.[67] Kantian commentators have argued that Nietzsche's practical philosophy requires the being of a cocky capable of standing back in the Kantian sense. For an individual to create values of their own, which is a primal idea in Nietzsche's philosophy, they must be able to conceive of themselves as a unified agent. Fifty-fifty if the amanuensis is influenced by their drives, he must regard them equally his own, which undermines Nietzsche's formulation of autonomy.[68]

John Stuart Manufactory [edit]

The Utilitarian philosopher John Stuart Mill criticizes Kant for not realizing that moral laws are justified by a moral intuition based on utilitarian principles (that the greatest proficient for the greatest number ought to be sought). Manufactory argued that Kant'south ethics could non explain why certain actions are wrong without appealing to utilitarianism.[69] As basis for morality, Mill believed that his principle of utility has a stronger intuitive grounding than Kant's reliance on reason, and can ameliorate explicate why certain deportment are correct or wrong.[70]

Jean-Paul Sartre [edit]

Jean-Paul Sartre rejects the central Kantian thought that moral activeness consists in obeying abstractly knowable maxims which are true independently of situation, that is, independent of historical, social, and political time and place. He believes that although the possible, and therefore the universal, is a necessary component of activeness, whatsoever moral theory which ignores or denies the peculiar style of existence or condition of persons would stand self-condemned.[71]

Michel Foucault [edit]

Although Michel Foucault calls himself a descendant of the tradition of critical philosophy established by Kant, he rejects Kant's attempt to place all rational conditions and constraints in the subject field.[72]

Virtue ethics [edit]

Virtue ethics is a form of ethical theory which emphasizes the graphic symbol of an agent, rather than specific acts; many of its proponents take criticised Kant's deontological arroyo to ethics. Elizabeth Anscombe criticised modern ethical theories, including Kantian ethics, for their obsession with law and obligation.[73] As well equally arguing that theories which rely on a universal moral constabulary are too rigid, Anscombe suggested that, because a moral law implies a moral lawgiver, they are irrelevant in modern secular guild.[74]

In his work After Virtue, Alasdair MacIntyre criticises Kant's formulation of universalisability, arguing that various piffling and immoral maxims can pass the test, such as "Keep all your promises throughout your unabridged life except one." He further challenges Kant's conception of humanity as an finish in itself by arguing that Kant provided no reason to treat others equally means: the maxim "Let everyone except me be treated as a means," though seemingly immoral, can be universalized.[75] Bernard Williams argues that, past abstracting persons from character, Kant misrepresents persons and morality and Philippa Foot identified Kant as one of a select group of philosophers responsible for the fail of virtue by analytic philosophy.[76]

Christian ethics [edit]

Roman Catholic priest Servais Pinckaers regarded Christian ethics as closer to the virtue ethics of Aristotle than Kant'due south ethics. He presented virtue ethics every bit freedom for excellence, which regards freedom equally acting in accordance with nature to develop i's virtues. Initially, this requires post-obit rules—but the intention is that the agent develop virtuously, and regard interim morally equally a joy. This is in contrast with freedom of indifference, which Pinckaers attributes to William Ockham and likens to Kant. On this view, freedom is ready against nature: complimentary deportment are those non determined by passions or emotions. There is no evolution or progress in an agent's virtue, merely the forming of habit. This is closer to Kant's view of ideals, considering Kant'south conception of autonomy requires that an agent is non just guided by their emotions, and is set in contrast with Pinckaer's conception of Christian ethics.[77]

Autonomy [edit]

A number of philosophers (including Elizabeth Anscombe, Jean Bethke Elshtain, Servais Pinckaers, Iris Murdoch, and Kevin Knight)[78] have all suggested that the Kantian conception of ideals rooted in autonomy is contradictory in its dual contention that humans are co-legislators of morality and that morality is a priori. They debate that if something is universally a priori (i.e., existing unchangingly prior to experience), then it cannot also be in part dependent upon humans, who accept non e'er existed. On the other hand, if humans truly practise legislate morality, then they are not bound by information technology considerately, because they are always free to change it.

This objection seems to rest on a misunderstanding of Kant'southward views since Kant argued that morality is dependent upon the concept of a rational will (and the related concept of a categorical imperative: an imperative which whatsoever rational existence must necessarily will for itself).[79] It is not based on contingent features of whatever being's will, nor upon human wills in item, so there is no sense in which Kant makes ethics "dependent" upon annihilation which has not e'er existed. Furthermore, the sense in which our wills are subject to the law is precisely that if our wills are rational, we must will in a lawlike manner; that is, we must will co-ordinate to moral judgments we apply to all rational beings, including ourselves.[80] This is more than easily understood past parsing the term "autonomy" into its Greek roots: auto (self) + nomos (dominion or law). That is, an democratic will, co-ordinate to Kant, is non just one which follows its own volition, but whose will is lawful-that is, befitting to the principle of universalizability, which Kant besides identifies with reason. Ironically, in another passage, willing according to immutable reason is precisely the kind of capacity Elshtain ascribes to God every bit the basis of his moral say-so, and she commands this over an inferior voluntarist version of divine command theory, which would make both morality and God'southward will contingent.[81] As O'Neill argues, Kant'south theory is a version of the first rather than the 2nd view of autonomy, and then neither God nor any human authority, including contingent man institutions, play any unique administrative office in his moral theory. Kant and Elshtain, that is, both agree God has no choice but to suit his will to the immutable facts of reason, including moral truths; humans do have such a option, merely otherwise their relationship to morality is the same as that of God'south: they can recognize moral facts, but do not decide their content through contingent acts of volition.

Applications [edit]

Medical ethics [edit]

Kant believed that the shared ability of humans to reason should be the ground of morality, and that it is the ability to reason that makes humans morally significant. He, therefore, believed that all humans should accept the right to common dignity and respect.[82] Margaret L. Eaton argues that, according to Kant's ethics, a medical professional must be happy for their ain practices to be used by and on anyone, fifty-fifty if they were the patient themselves. For instance, a researcher who wished to perform tests on patients without their knowledge must be happy for all researchers to do so.[83] She also argues that Kant'southward requirement of autonomy would mean that a patient must be able to make a fully informed decision almost handling, making it immoral to perform tests on unknowing patients. Medical research should be motivated out of respect for the patient, so they must be informed of all facts, fifty-fifty if this would be probable to dissuade the patient.[84]

Jeremy Sugarman has argued that Kant'due south formulation of autonomy requires that patients are never used simply for the do good of society, but are always treated as rational people with their ain goals.[85] Aaron Eastward. Hinkley notes that a Kantian account of autonomy requires respect for choices that are arrived at rationally, not for choices which are arrived at by idiosyncratic or non-rational ways. He argues that there may be some difference between what a purely rational amanuensis would cull and what a patient actually chooses, the difference being the issue of not-rational idiosyncrasies. Although a Kantian physician ought not to lie to or coerce a patient, Hinkley suggests that some grade of paternalism—such as through withholding data which may prompt a not-rational response—could be adequate.[86]

Ballgame [edit]

In How Kantian Ethics Should Treat Pregnancy and Abortion, Susan Feldman argues that abortion should be defended co-ordinate to Kantian ethics. She proposes that a woman should exist treated as a dignified autonomous person, with control over their body, every bit Kant suggested. She believes that the free choice of women would be paramount in Kantian ethics, requiring abortion to exist the mother's decision.[87]

Dean Harris has noted that, if Kantian ideals is to be used in the give-and-take of abortion, it must be decided whether a fetus is an democratic person.[88] Kantian ethicist Carl Cohen argues that the potential to exist rational or participation in a more often than not rational species is the relevant distinction betwixt humans and inanimate objects or irrational animals. Cohen believes that even when humans are non rational because of age (such every bit babies or fetuses) or mental disability, agents are still morally obligated to treat them every bit an ends in themselves, equivalent to a rational developed such equally a female parent seeking an abortion.[89]

Sexual ethics [edit]

Kant viewed humans as being subject to the animalistic desires of self-preservation, species-preservation, and the preservation of enjoyment. He argued that humans have a duty to avoid maxims that harm or dethrone themselves, including suicide, sexual degradation, and drunkenness.[90] This led Kant to regard sexual intercourse as degrading because it reduces humans to an object of pleasance. He admitted sex simply inside marriage, which he regarded as "a merely animal union." He believed that masturbation is worse than suicide, reducing a person's status to below that of an animal; he argued that rape should be punished with castration and that bestiality requires expulsion from society.[91]

Commercial sexual practice [edit]

Feminist philosopher Catharine MacKinnon has argued that many contemporary practices would be accounted immoral by Kant's standards considering they dehumanize women. Sexual harassment, prostitution, and pornography, she argues, objectify women and practice non meet Kant's standard of human autonomy. Commercial sex has been criticised for turning both parties into objects (and thus using them as a means to an cease); mutual consent is problematic because in consenting, people choose to objectify themselves. Alan Soble has noted that more liberal Kantian ethicists believe that, depending on other contextual factors, the consent of women can vindicate their participation in pornography and prostitution.[92]

Animal ethics [edit]

Because Kant viewed rationality every bit the basis for existence a moral patient—1 due moral consideration—he believed that animals have no moral rights. Animals, according to Kant, are not rational, thus one cannot behave immorally towards them.[93] Although he did non believe we have any duties towards animals, Kant did believe being brutal to them was wrong because our behaviour might influence our attitudes toward human beings: if we go accustomed to harming animals, then we are more probable to run across harming humans as adequate.[94]

Ethicist Tom Regan rejected Kant's cess of the moral worth of animals on three main points: Get-go, he rejected Kant'south merits that animals are not self-witting. He then challenged Kant's claim that animals have no intrinsic moral worth considering they cannot make a moral judgment. Regan argued that, if a being'south moral worth is determined past its ability to make a moral judgment, then nosotros must regard humans who are incapable of moral thought as being equally undue moral consideration. Regan finally argued that Kant'southward exclamation that animals be merely equally a means to an end is unsupported; the fact that animals accept a life that can get well or badly suggests that, similar humans, they have their own ends.[95]

Christine Korsgaard has reinterpreted Kantian theory to argue that beast rights are implied by his moral principles.[96]

Lying [edit]

Kant believed that the Categorical Imperative provides us with the maxim that nosotros ought not to lie in any circumstances, even if we are trying to bring about adept consequences, such as lying to a murderer to foreclose them from finding their intended victim. Kant argued that, because we cannot fully know what the consequences of any activity will be, the result might be unexpectedly harmful. Therefore, we ought to human activity to avoid the known wrong—lying—rather than to avoid a potential incorrect. If at that place are harmful consequences, we are clean-living considering nosotros acted according to our duty.[97] Driver argues that this might non be a problem if nosotros choose to formulate our maxims differently: the maxim 'I will lie to save an innocent life' tin be universalized. Nevertheless, this new maxim may all the same treat the murderer as a ways to an cease, which nosotros have a duty to avoid doing. Thus we may nevertheless be required to tell the truth to the murderer in Kant's example.[98]

References [edit]

- ^ Brinton 1967, p. 519.

- ^ a b Singer 1983, pp. 42.

- ^ Blackburn 2008, p. 240.

- ^ Benn 1998, pp. 101–102.

- ^ Guyer 2011, p. 194.

- ^ Forest 1999, p. 26-27.

- ^ Forest 1999, p. 37.

- ^ Driver 2007, p. 92.

- ^ Commuter 2007, p. 93.

- ^ Hill 2009, p. iii.

- ^ Wood 2008, p. 67.

- ^ Driver 2007, p. 83.

- ^ Johnson 2008.

- ^ Commuter 2007, p. 87.

- ^ a b Rachels 1999, p. 124.

- ^ Kant, Immanuel. [1785] 1879. Key Principles of the Metaphysic of Morals, translated by T. K. Abbott. p. 55.

- ^ Commuter 2007, p. 88.

- ^ Driver 2007, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Kant, Immanuel (1785). Thomas Kingsmill Abbott (ed.). Cardinal Principles of the Metaphysic of Morals (10 ed.). Projection Gutenberg. p. 39.

- ^ Kant, Immanuel (1785). Thomas Kingsmill Abbott (ed.). Fundamental Principles of the Metaphysic of Morals (10 ed.). Project Gutenberg. p. 35.

- ^ Palmer 2005, pp. 221–ii.

- ^ Hirst 1934, pp. 328–335.

- ^ Walker & Walker 2018.

- ^ Commuter 2007, p. ninety.

- ^ a b Benn 1998, p. 95.

- ^ Kant, Immanuel (1785). Thomas Kingsmill Abbott (ed.). Central Principles of the Metaphysic of Morals (ten ed.). Projection Gutenberg. pp. 60–62.

- ^ Kant & Paton 1991, p. 34.

- ^ Kant 1788, Volume one, Ch. 1, §1.

- ^ Kant 1785, Section 1, §17.

- ^ Sullivan 1989, p. 165.

- ^ Kant 1785, §ii.

- ^ Johnson 2008.

- ^ Atwell 1986, p. 152.

- ^ Korsgaard 1996, p. 24.

- ^ Rohlf 2010.

- ^ Wilson & Denis.

- ^ Hare 2011, p. 62.

- ^ a b Pojman 2008, p. 122.

- ^ Kain, Philip, pp. 277–301.

- ^ Payrow Shabani 2003, p. 53.

- ^ Collin 2007, p. 78.

- ^ a b Payrow Shabani 2003, p. 54.

- ^ Payrow Shabani 2003, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Hacohen 2002, p. 511.

- ^ Richardson, 2005.

- ^ Freeman 2019.

- ^ Brooks & Freyenhagen 2005, pp. 155–156.

- ^ Martyn 2003, p. 171.

- ^ Scott Lee 1991, p. 167.

- ^ Pyka 2005, pp. 85–95.

- ^ Liu 2012, pp.93–119.

- ^ O'Neill 2000, p. 75.

- ^ O'Neill 2000, pp. 76–77.

- ^ O'Neill 2000, p. 77.

- ^ O'Neill 2000, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Stocker 1976, p. 462.

- ^ Baron 1999, pp. 120–123.

- ^ Businesswoman 1999, pp. 131–132.

- ^ Stern 2012, pp. 109–121.

- ^ Stern 2012, pp. 130–131.

- ^ Brooks 2012, p. 75.

- ^ Vocalist 1983, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Manninon 2003, pp. 101–102.

- ^ Janaway 2002, p. 88.

- ^ Leiter 2004.

- ^ Janaway & Robertson 2012, pp. 202–204.

- ^ Janaway & Robertson 2012, p. 205.

- ^ Janaway & Robertson 2012, p. 206.

- ^ Ellis 1998, p. 76.

- ^ Miller 2013 p. 110.

- ^ Linsenbard 2007, pp. 65–68.

- ^ Robinson n.d.

- ^ Anscombe 1958, pp. 1–19.

- ^ Athanassoulis 2010.

- ^ MacIntyre 2013, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Louden 2011, p. iv.

- ^ Pinckaers 2003, pp. 67–75.

- ^ Anscombe, 1958, p.2; Elshtain, 2008, p. 258, annotation 22; Pinckaers 2003, p. 48; Murdoch, 1970, p.80; Knight 2009.

- ^ Immanuel Kant, 1786, p. 35.

- ^ O'Neill, 2000, 43.

- ^ Elshtain, 2008, 260 notation 75.

- ^ Eaton 2004, p. 39.

- ^ Eaton 2004, p. 40.

- ^ Eaton 2004, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Sugarman 2010, p. 44.

- ^ Engelhardt 2011, pp. 12–thirteen.

- ^ Kneller & Axinn 1998, pp. 265–266.

- ^ Harris 2011, p. 15.

- ^ Carl Cohen 1986, pp. 865–869.

- ^ Denis 1999, p. 225.

- ^ Wood 1999, p. ii.

- ^ Soble 2006, 549.

- ^ Commuter 2007, p. 97.

- ^ Driver 2007, p. 98.

- ^ Regan 2004, p. 178.

- ^ Korsgaard 2004; Korsgaard 2015, pp. 154–174; Pietrzykowski 2015, pp. 106–119.

- ^ Rachels 1999, p. 128.

- ^ Driver 2007, p. 96.

Bibliography [edit]

- Anscombe, G. Due east. M. (1958). "Modernistic Moral Philosophy". Philosophy. 33 (124): ane–19. doi:10.1017/S0031819100037943. ISSN 0031-8191. JSTOR 3749051.

- Athanassoulis, Nafsika (7 July 2010). "Virtue Ethics". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy . Retrieved 11 September 2013.

- Atwell, John (1986). Ends and principles in Kant's moral thought. Springer. ISBN9789024731671.

- Axinn, Sidney; Kneller, Jane (1998). Autonomy and Community: Readings in Contemporary Kantian Social Philosophy. SUNY Printing. ISBN9780791437438.

- Businesswoman, Marcia (1999). Kantian Ethics Almost Without Apology. Cornell University Press. ISBN9780801486043.

- Bergande, Wolfram (2017). Kant'southward apathology of pity. Schreel, Louis (Ed.): Pathology & Aesthetics. Essays on the Pathological in Kant and Gimmicky Aesthetics. Duesseldorf Academy Press. ISBN978-3957580320 . Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- Benn, Piers (1998). Ethics. UCL Press. ISBNone-85728-453-4.

- Blackburn, Simon (2008). "Morality". Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy (Second edition revised ed.).

- Brinton, Crane (1967). "Enlightenment". Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Vol. 2. Macmillan.

- Brooks, Thom (2012). Hegel'due south Philosophy of Right. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN9781405188135.

- Brooks, Thom; Freyenhagen, Fabian (2005). The Legacy of John Rawls. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN9780826478436.

- Cohen, Carl (1986). "The Instance For the Employ of Animals in Biomedical Research". New England Periodical of Medicine. 315 (xiv): 865–69. doi:10.1056/NEJM198610023151405. PMID 3748104.

- Collin, Finn (2007). "Danish yearbook of philosophy". 42. Museum Tusculanum Press. ISSN 0070-2749.

- Denis, Lara (April 1999). "Kant on the Wrongness of "Unnatural" Sex". History of Philosophy Quarterly. Academy of Illinois Printing. 16 (2): 225–248.

- Driver, Julia (2007). Ethics: The Fundamentals. Blackwell. ISBN978-1-4051-1154-6.

- Eaton, Margaret (2004). Ethics and the Business of Bioscience. Stanford University Printing. ISBN9780804742504.

- Ellis, Ralph D. (1998). Only Results: Ethical Foundations for Policy Analysis . Georgetown University Printing. ISBN9780878406678.

- Elshtain, Jean Bethke (2008). Sovereignty: God, State, and Cocky. Basic Books. ISBN978-0465037599.

- Engelhardt, Hugo Tristram (2011). Bioethics Critically Reconsidered: Having Second Thoughts. Springer. ISBN9789400722446.

- Freeman, Samuel (2019). "Original Position". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy . Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- Guyer, Paul (2011). "Affiliate 8: Kantian Perfectionism". In Jost, Lawrence; Wuerth, Julian (eds.). Perfecting Virtue: New Essays on Kantian Ideals and Virtue Ethics . Cambridge University Press. ISBN9781139494359.

- Hacohen, Malachi Haim (2002). Karl Popper - The Formative Years, 1902-1945: Politics and Philosophy in Interwar Vienna. Cambridge University Press. ISBN9780521890557.

- Hare, John (1997). The Moral Gap: Kantian Ideals, Human Limits, and God's Assistance. Oxford University Printing. ISBN9780198269571.

- Hare, John (2011). "Kant, The Passions, And The Construction Of Moral Motivation". Faith and Philosophy: Periodical of the Lodge of Christian Philosophers. 28 (one): 54–70.

- Harris, Dean (2011). Ethics in Health Services and Policy: A Global Arroyo. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN9780470531068.

- Hill, Thomas (2009). The Blackwell Guide to Kant'south Ideals. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN9781405125819.

- Hirst, East. W. (1934). "The Categorical Imperative and the Golden Dominion". Philosophy. 9 (35): 328–335. doi:x.1017/S0031819100029442. ISSN 0031-8191. JSTOR 3746418.

- Janaway, Christopher (2002). Schopenhauer: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Printing. ISBN0-19-280259-3.

- Janaway, Christopher; Robertson, Simon (2013). Nietzsche, Naturalism, and Normativity. Oxford University Press. ISBN9780199583676.

- Johnson, Robert (2008). "Kant's Moral Philosophy". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy . Retrieved 11 September 2013.

- Johnson, Robert N. (2009). "i: Expert Volition and the Moral Worth of Acting from Duty". In Hill Jr, Thomas E. (ed.). The Blackwell Guide to Kant'due south Ethics. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN9781405125826.

- Kain, Philip J. (1986). "The Young Marx and Kantian Ethics". Studies in Soviet Thought. 31 (four): 277–301. doi:10.1007/BF01368079. ISSN 0039-3797. JSTOR 20100119.

- Kant, Immanuel (1785). – via Wikisource.

- Kant, Immanuel (1788). – via Wikisource.

- Knight, Kevin (2009). "Cosmic Encyclopedia: Categorical Imperative". Cosmic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- Korsgaard, Christine (1996). Creating the Kingdom of Ends . Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-0-52149-962-0.

- Korsgaard, Christine (2004). "Young man Creatures: Kantian Ethics and Our Duties to Animals". The Tanner Lectures on Homo Values. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- Korsgaard, Christine M. (2015). "A Kantian Case for Animal Rights". In Višak, Tatjana; Garner, Robert (eds.). The Ethics of Killing Animals. pp. 154–174.

- Leiter, Briain (2004). "Nietzsche's Moral and Political Philosophy". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy . Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- Linsenbard, Gail (2007). "Sartre's Criticisms of Kant's Moral Philosophy". Sartre Studies International. 13 (2): 65–85. ISSN 1357-1559. JSTOR 23510940.

- Liu, JeeLoo (May 2012). "Moral Reason, Moral Sentiments and the Realization of Altruism: A Motivational Theory of Altruism". Asian Philosophy. 22 (2): 93–119. doi:10.1080/09552367.2012.692534.

- Loewy, Erich (1989). Textbook of Medical Ethics. Springer. ISBN9780306432804.

- Louden, Robert B. (2011). Kant'southward Human Existence:Essays on His Theory of Homo Nature. Oxford Academy Printing. ISBN9780199911103.

- MacIntyre, Alasdair (2013). After Virtue. A&C Black. ISBN9781623565251.

- Manninon, Gerard (2003). Schopenhauer, religion and morality: the humble path to ethics. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN9780754608233.

- Miller, Dale (2013). John Stuart Manufactory. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN9780745673592.

- Murdoch, Iris (1970). The Sovereignty of the Proficient. Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN978-0415253994.

- O'Neill, Onora (2000). Bounds of Justice. Cambridge Academy Press. ISBN9780521447447.

- Palmer, Donald (2005). Looking At Philosophy: The Unbearable Heaviness of Philosophy Made Lighter (Quaternary ed.). McGraw-Hill Pedagogy. ISBN9780078038266.

- Payrow Shabani, Omid (2003). Democracy, power and legitimacy: the critical theory of Jürgen Habermas. University of Toronto Press. ISBN9780802087614.

- Picnkaers, Servais (2003). Morality: The Catholic View. St. Augustine Press. ISBN978-1587315152.

- Pietrzykowski, Tomasz (2015). "Kant, Korsgaard and the Moral Condition of Animals". Archihwum Filozofii Prawa I Filozofi Społecznej. two (11): 106–119. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- Pojman, Louis (2008). Ethics: Discovering Right and Incorrect. Cengage Learning. ISBN9780495502357.

- Pyka, Marek (2005). "Thomas Nagel on Listen, Morality, and Political Theory". American Journal of Theology & Philosophy. 26 (1/ii): 85–95. ISSN 0194-3448. JSTOR 27944340.

- Rachels, James (1999). The Elements of Moral Philosophy (Third ed.). McGraw-Loma. ISBN0-07-116754-4.

- Regan, Tom (2004). The case for brute rights. University of California Press. ISBN978-0-52024-386-six.

- Richardson, Henry (18 Nov 2005). "John Rawls (1921–2002)". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy . Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- Riedel, Manfred (1984). Between Tradition and Revolution: The Hegelian Transformation of Political Philosophy . Cambridge University Press. ISBN9780521174886.

- Robinson, Bob (n.d.). "Michel Foucault: Ideals". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Rohlf, Michael (20 May 2010). "Immanuel Kant". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy . Retrieved ii Apr 2012.

- Vocalist, Peter (1983). Hegel: A Very Curt Introduction . Oxford Academy Press. ISBN9780191604416.

- Soble, Alan (2006). Sexual practice from Plato to Paglia: A Philosophical Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. Greenwood Publishing Grouping. ISBN9780313334245.

- Stern, Robert (2012). Agreement Moral Obligation. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Stocker, Michael (12 August 1976). "The Schizophrenia of Modern Ethical Theories". The Journal of Philosophy. Journal of Philosophy. 73 (14): 453–466. doi:ten.2307/2025782. JSTOR 2025782.

- Sugarman, Jeremy (2010). Methods in Medical Ethics. Georgetown Academy Press. ISBN9781589017016.

- Sullivan, Roger (1994). An Introduction to Kant's Ideals . Cambridge University Press. ISBN9780521467698.

- Sullivan, Roger (1989). Immanuel Kant's Moral Theory. Cambridge University Printing. ISBN9780521369084.

- Taylor, Robert (2011). Reconstructing Rawls: the Kantian foundations of justice as fairness. Penn State Press. ISBN9780271037714.

- Walker, Paul; Walker, Ally (2018). "The Gilded Rule Revisited". Philosophy Now.

- Wilson, Eric Entrican; Denis, Lara (2018). "Kant and Hume on Morality". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- Wood, Allen (2008). Kantian Ethics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN9780521671149.

- Wood, Allen (1999). Kant'southward Ethical Thought. Cambridge University Press. ISBN9780521648363.

External links [edit]

- Kantian Ethics

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kantian_ethics